Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block

Indications: Upper extremity surgical procedures below the level of the shoulder.

Special Considerations: Effective at anesthetizing the entire arm below the level of the shoulder, with the brachial plexus (trunks and divisions) being blocked at the level of the first rib. Although, there is a risk of pneumothorax at this level, the routine use of ultrasound enables visualization of the pleura and needle, allowing for the block to be performed quite safely. Given the close proximity of the lung pleura to the nerve structures, it is important to have dynamic view of the tip of the needle during advancement towards the nerve bundle, a skill which requires advanced skills in regional anesthesia in the pediatric population.

An effective block may include blockade of the phrenic nerve (up to 67%) and should be carefully considered in patients presenting with significant respiratory disease. For this reason, bilateral blockade should be avoided.

Patient Position: Ideally, patient in head-up position with the head turned away from the block site (contralateral side). A pillow below the head will also help with positioning and visualization. The arm can be placed at the patient’s side. In a pediatric patient under general anesthesia, a shoulder roll may be helpful to help extend and stabilize the head, while also providing more space for the operator to maneuver the ultrasound probe and needle in the supraclavicular fossa.

Dose: 0.5 - 1.5 mg/kg of Bupivacaine or Ropivacaine (roughly 0.2 - 0.4 mL/kg).

Technique: Probe – Linear; Needle – In-plane

Under sterile conditions, identify the clavicle and place the upright probe behind the clavicle, with the probe upright and parallel to the bony landmark, so that it is lying in the supraclavicular fossa. The probe should be placed in such a manner to allow for visualization of structures deep into the thorax, in a caudal direction. The first landmark to identify will be the subclavian artery, seen as a black, pulsating hypoechoic circle (figure 1), which is the cross-sectional view of the artery. Slide the probe in medial to lateral directions if artery is not immediately seen. Keep in mind that the subclavian vein is medial to the subclavian artery.

Once the artery has been identified, look immediately lateral to the vessel and a honeycomb like structure will be seen, which is the brachial plexus at the level of the trunk and divisions. The first rib will be present immediately inferior (caudad) to the plexus, and at certain angles will case a hyperechoic shadow. Medial to the first rib, and inferior (caudad) to the subclavian artery will be the pleura, a key anatomical structure to be aware of in order to avoid! Once all the structures are identified, make adjustments with the ultrasound probe to obtain a clear view of the nerve bundle and the fascial layers surrounding it. In order to allow for visualization of the needle as it enters the supraclavicular fossa, you may position the probe so that the subclavian artery is at the edge of your window but keeping the lateral wall of the vessel (next to the nerve bundle) in view. The needle tip should penetrate the sheath of the bundle so that local anesthetic injection will surround the trunks and divisions.

There are options in terms of where the needle tip should be placed in relation to the bundle and having dynamic visualization with ultrasound allows for more than one site of injection. Some elect to inject a second time by withdrawing the needle and then injecting local anesthetic superficial or on top of the nerve bundle, while others first inject at around the 5 to 6 o’clock position—the “corner pocket”—to ensure adequate local anesthetic spread to the inferior trunk. The goal is to surround the bundle with a pool of local anesthetic in order to obtain a dense, effective block.

Coverage: Brachial plexus, at level of trunks/divisions.

Potential Complications:

Intravascular injection or injury

Pneumothorax

Bleeding / infection at needle insertion site

Phrenic nerve blockade

Positioning, Probe Orientation & Sensory Loss

Positioning & Probe Orientation

Expected Sensory Loss

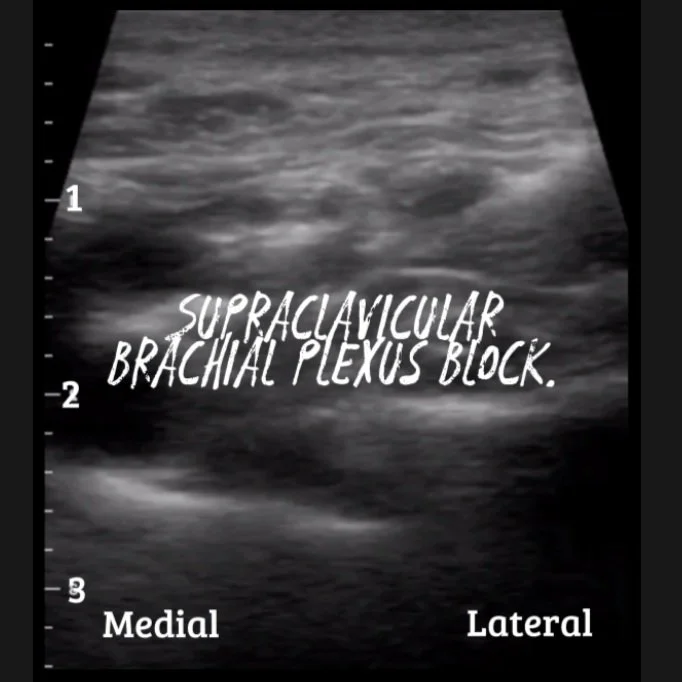

Ultrasound Images

Commonly known as the “spinal of the arm,” the supraclavicular nerve block was first described in a 1928 paper by Kulenkampff, as an anesthetic for surgeries of the arm, forearm and hand. The original paper described the block utilizing landmark techniques and tactile feel during block performance, though the associated risk of pneumothorax was likely responsible for the technique falling out of favor. Almost a century later, brachial plexus blocks are now safely performed in the pediatric population with ultrasound guidance, allowing visualization of the needle as it travels in close proximity to vital structures in the neck and thorax.

A 2008 paper by De José Mariá et al compared supraclavicular to infraclavicular nerve blocks in pediatric patients for upper extremity surgery. Both blocks were found to be effective, with the time to perform the block found to be shorter in the supraclavicular group. Papers published by the Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network (Walker, 2018) demonstrated the safety of supraclavicular nerve blocks in children and adolescents. No reported cases of permanent nerve damage were reported and only one case of pneumothorax was reported in the supraclavicular group (n =2860), which was managed conservatively without the need for a chest tube.

Adult literature usually describes a set volume for nerve blocks, but given the variability in a pediatric patient’s size, dosing of local anesthetics is weight based. Literature recommends the use of either 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine with epinephrine (1:200k) at a dose of 0.2-0.5 ml/kg. With dynamic ultrasound visualization, lower volumes may be accepted given that local anesthetic is seen to encircle the divisions of the brachial plexus.

In conclusion, while the supraclavicular nerve block might be considered an advanced block—especially in children given the close proximity to vital structures—in experienced hands, it is a safe technique that is highly effective and reliably provides dense perioperative analgesia, decreases opioid and anesthetic consumption, and contributes to faster emergence from general anesthesia.

“Spinal of the arm,” indeed.

Urmey, W.F., Talts, K.H. and Sharrock, N.E., 1991. One hundred percent incidence of hemidiaphragmatic paresis associated with interscalene brachial plexus anesthesia as diagnosed by ultrasonography. Anesthesia and analgesia, 72(4), pp.498-503.

Kulenkampff, D. (1928). Brachial plexus anaesthesia: its indications, technique, and dangers. Annals of surgery, 87(6), 883.

De Jose Maria, B., BanUS, E., Navarro Egea, M., Serrano, S., PerellO, M. and Mabrok, M., 2008. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular vs infraclavicular brachial plexus blocks in children. Pediatric Anesthesia, 18(9), pp.838-844.

Grant, S. A., Auyong, D. B., Gonzales, J., Grant, S. A., & Auyong, D. B. (2017). Supraclavicular Nerve Block. In Ultrasound guided regional anesthesia (pp. 46–53). essay, Oxford University Press.

Krodel, D. J., Marcelino, R., Sawardekar, A., & Suresh, S. (2017). Pediatric regional anesthesia: A review and Update. Current Anesthesiology Reports, 7(2), 227-237.

Taenzer, A., Walker, B.J., Bosenberg, A.T., Krane, E.J., Martin, L.D., Polaner, D.M., Wolf, C. and Suresh, S., 2014. Interscalene brachial plexus blocks under general anesthesia in children: is this safe practice?. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine, 39(6), pp.502-505.

Tobias, J. D. (2001). Brachial plexus anaesthesia in children. Pediatric Anesthesia, 11(3), 265-275.

Tsui, B.C., Suresh, S. and Warner, D.S., 2010. Ultrasound imaging for regional anesthesia in infants, children, and adolescents: a review of current literature and its application in the practice of extremity and trunk blocks. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 112(2), pp.473-492.

Walker, B.J., Long, J.B., Sathyamoorthy, M., Birstler, J., Wolf, C., Bosenberg, A.T., Flack, S.H., Krane, E.J., Sethna, N.F., Suresh, S. and Taenzer, A.H., 2018. Complications in pediatric regional anesthesia: an analysis of more than 100,000 blocks from the pediatric regional anesthesia network. Anesthesiology, 129(4), pp.721-732.