Serratus Anterior Plane Block

Indications: Thoracoscopy (VATS, medical thoracoscopy/pleuroscopy), Thoracotomy (CoA, CCAM, TEF repair), Implantable devices (mediports, broviacs, PPM, AICD), Nuss Procedure for Pectus Excavatum.

Special Considerations: Determine whether hydrodissection or nerve blockade will interfere in the surgical plan. As discussed below, the superficial, while potentially longer lasting, may introduce some idiosyncrasies for specific procedures.

Patient Position: Supine or lateral. One can also place a small bump under the ipsilateral thorax to give you a bit more posterior access while remaining supine. Ideally, abducting the arm will open the axilla for probe access.

Technique: In-plane; Parasagittal or Transverse.

Parasagittal: While I initially learned the transverse superficial technique a la Blanco’s description, the anesthesiologists at my new institution only performed the deep via a parasagittal technique. Due to their huge volume of breast cases, and the surgeon complaints about tissue plane disruption with the superficial technique, they were forced to evolve. This is typically performed in the same plane as the midaxillary line. While traditionally done at the 4th or 5th rib, we will sometimes place our blocks even lower to accomodate for chest tubes, etc. We will also typically do multiple injections at different rib spaces, as this ensures local at our desired locations. After identification of the desired rib, advance the needle in-plane aiming for the middle of the rib. Make sure you can visualize the needle tip throughout the procedure to avoid advancing too deep and injuring the pleura. After contact is made on the superficial surface of the rib, and after (-) aspiration, hydrodissection should elevate the serratus anterior off the ribs.

Transverse: Place the probe transversely at the level of the nipple (approximately T4). Drag the probe laterally and posteriorly. The muscle layer directly on top of the ribs is the serratus anterior. When performing a superficial block, I try and identify the thoracodorsal artery (runs in the plane between latissimus and serratus anterior muscles). This landmark serves two purposes. One, it confirms the correct plane for a superficial block. Two, it shows you the one critical structure to avoid during superficial block placement: the thoracodorsal artery. Once you visualize the artery, follow that plane a bit more posteriorly, typically entering the skin in the region between the anterior and midaxillary lines, and advance the needle superficial to the artery prior to entering the superficial serratus plane.

If performing a deep block, the critical structure to identify (and avoid) is the pleura. After you have identified the pleura, advance the needle tip toward the middle of the rib (typically the 4th or 5th rib) and after negative aspiration, hydrodissect the plane deep to the serratus. It should lift the serratus anterior muscle off the ribs (similar to an ESP block). Care must be taken to visualize the needle tip throughout and avoid accidentally advancing beyond the intercostal muscle into the pleura. While extraordinarily rare, pneumothorax after deep SAPB has been described.

Coverage: The lateral cutaneous branches of intercostal nerves. If done superficially, the long thoracic nerve and thoracodorsal nerve may also incidentally be targeted, though their analgesic contribution is uncertain. With increased volume, may cover larger sensory loss.

Potential Complications:

Intravascular injection or injury

Pneumothorax (if needle directed too deep)

Bleeding / infection at needle insertion site

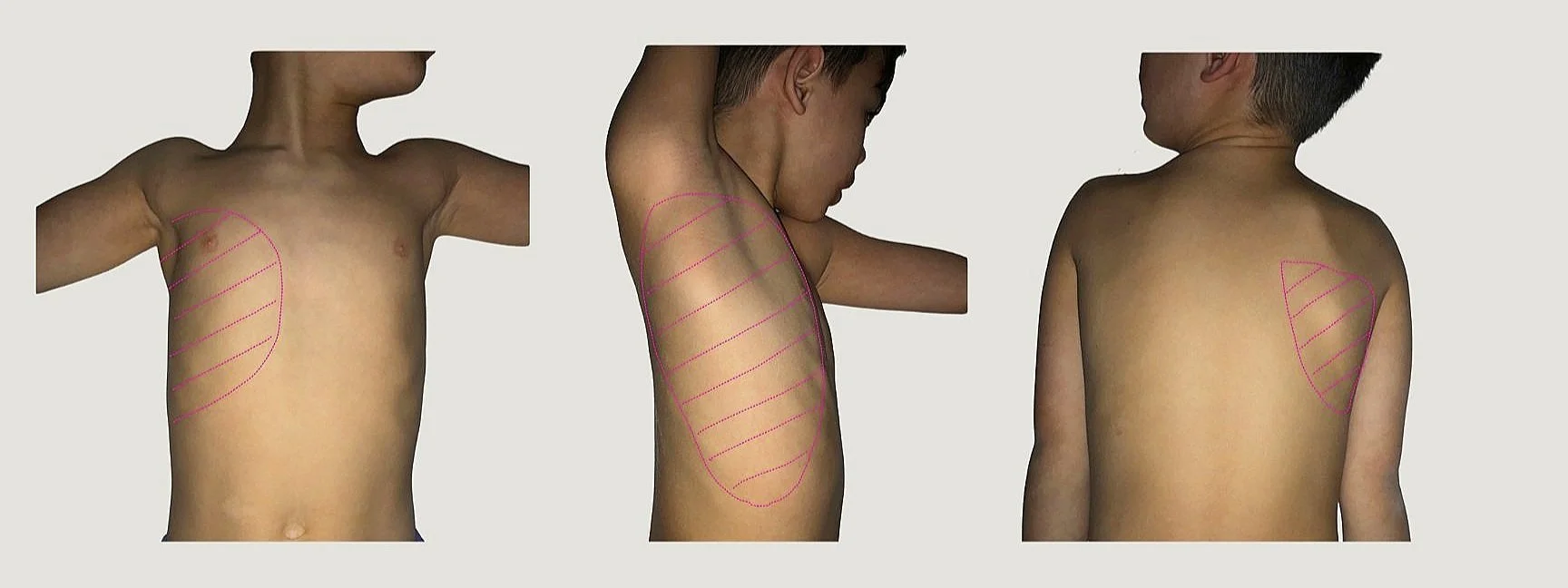

Expected Dermatomal Coverage

Patient Positioning/Sonoanatomy

(Images taken in supine position, though patient can be positioned in modified or full lateral)

Needle trajectory (white dotted line); Superficial (blue dashed line); Deep (pink dashed line)

Needle trajectory (white dotted line); Superficial (blue dashed line); Deep (pink dashed line)

Originally described by Blanco et al in 2013 in their search for complete paresthesia of the hemithorax, the Serratus Anterior Plane Block (SAPB) has found a role in everything from breast reconstruction, to implantable cardiac devices, to intrathoracic procedures, and more. While few would argue against its utility, there is still ongoing debate regarding the optimal technique: deep vs. superficial, single injection vs multi-injection.

The original paper by Blanco found that the superficial SAPB was not only technically easier to perform, but lasted longer. The authors were quick to remind readers that this was really just a proof-of-concept paper and was not designed to study clinical efficacy between the two. They recommended further randomized trials to determine which block is more effective.

Flash forward almost 9 years and we still do not have a definitive answer. While some initial studies seemed to confirm that superficial may be superior, follow up studies have had mixed results. Looking at VATS lobectomies, Qui et al found patients who received superficial SAPB to have better VAS pain scores, while Moon et al found their intraoperative analgesic efficacy to be similar. When people looked at SAPB in breast cases, things got a little more nuanced. Abdullah et al looked at deep vs superficial in ambulatory breast cases and found the deep SAPB non-inferior, but not superior to superficial. And while patients who received deep SAPB’s used more perioperative opioids and had more postoperative pain, a deep SAPB in these patients offered some unique advantages. Many breast cases involve axillary dissection. Performing a superficial SAPB (typically performed in the midaxillary plane) may disrupt surgical tissue planes, potentially block the long thoracic and thoracodorsal nerves (which surgeons try to identify and preserve), and potentially advance a needle through metastatic lymph nodes and increase the risk of tumor seeding. While perhaps not as effective an analgesic technique as the superficial, it is comforting to know that employing a deep technique in these patients is still a viable and effective technique. More recently, Edwards et al found 30% less opioid consumption and improved pain scores in mastectomy patients randomized to a deep SAPB. So, the story continues.

In children, the literature is still limited to mostly case reports. Biswas et al performed deep SAPB in pediatric CoA repairs via thoracotomy with very effective intraoperative analgesic relief. The patients ages ranged from 3 days to 4 years old, and from 1.9 to 16kg. Beyond the intubating dose of fentanyl (2mcg/kg), no further intraoperative opioids were given. Moreover, all three patients received minimal postoperative opioids during their hospitalization. Kaushal et al looked at deep SAPB vs PECII vs Intercostal Nerve blocks for postoperative thoracotomy pain. They found that while SAPB and PEC II yielded similar results, they were both superior to intercostals. In a randomized study looking at SAPB for thoracotomies, Gado et al found that deep SAPB provided a significant decrease in postoperative FLACC scores, reduced intraoperative and post-operative opioid use, as well as delay of the first rescue dose.

While their patient population wasn’t entirely “pediatric,” Altun et al looked at the efficacy of superficial SAPB in Nuss repairs for Pectus Excavatum compared to their standard post-op pain management: PCA. Not surprisingly, they found the SAPB group required less opioids in the first 24hrs. With the advent of multimodal analgesic protocols, coupled with the inherent risks of thoracic epidurals, there is, at least in my mind, the question of whether alternative regional techniques can add anything of value. To date, no one has directly compared deep vs superficial SAPB in Pectus repairs.

While the analgesic superiority between the two might not be definitively known, the SAPB has clearly earned a place in the pantheon of chest wall blocks for its versatility. It can be done superficially, deep, transverse, or parasagittally. For medical pleuroscopies, I routinely do a combo of all of them!

And, like a boss, it even works in dogs!

Blanco, R., Parras, T., McDonnell, J.G. and Prats‐Galino, A., 2013. Serratus plane block: a novel ultrasound‐guided thoracic wall nerve block. Anaesthesia, 68(11), pp.1107-1113.

Kunhabdulla, N.P., Agarwal, A., Gaur, A., Gautam, S.K. and Gupta, R., 2014. Serratus anterior plane block for multiple rib fractures. Pain Physician, 17(5), pp.E651-3.

Moon, S., Lee, J., Kim, H., Kim, J., Kim, J. and Kim, S., 2020. Comparison of the intraoperative analgesic efficacy between ultrasound-guided deep and superficial serratus anterior plane block during video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Medicine, 99(47).

Qiu, L., Bu, X., Shen, J., Li, M., Yang, L., Xu, Q., Chen, Y. and Yang, J., 2021. Observation of the analgesic effect of superficial or deep anterior serratus plane block on patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy. Medicine, 100(3).

Abdallah, F.W., Cil, T., MacLean, D., Madjdpour, C., Escallon, J., Semple, J. and Brull, R., 2018. Too deep or not too deep?: a propensity-matched comparison of the analgesic effects of a superficial versus deep serratus fascial plane block for ambulatory breast cancer surgery. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine, 43(5), pp.480-487.

Edwards, J.T., Langridge, X.T., Cheng, G.S., McBroom, M.M., Minhajuddin, A. and Machi, A.T., 2021. Superficial vs. deep serratus anterior plane block for analgesia in patients undergoing mastectomy: A randomized prospective trial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 75, p.110470.

Biswas, A., Castanov, V., Li, Z., Perlas, A., Kruisselbrink, R., Agur, A. and Chan, V., 2018. Serratus plane block: a cadaveric study to evaluate optimal injectate spread. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine, 43(8), pp.854-858.

Biswas, A., Luginbuehl, I., Szabo, E., Caldeira-Kulbakas, M., Crawford, M.W. and Everett, T., 2018. Use of serratus plane block for repair of coarctation of aorta: a report of 3 cases. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine, 43(6), pp.641-643.

Kim, D.H., Oh, Y.J., Lee, J.G., Ha, D., Chang, Y.J. and Kwak, H.J., 2018. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided serratus plane block on postoperative quality of recovery and analgesia after video-assisted thoracic surgery: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 126(4), pp.1353-1361.

Khalil, A.E., Abdallah, N.M., Bashandy, G.M. and Kaddah, T.A.H., 2017. Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block versus thoracic epidural analgesia for thoracotomy pain. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia, 31(1), pp.152-158.

Kaushal, B., Chauhan, S., Saini, K., Bhoi, D., Bisoi, A.K., Sangdup, T. and Khan, M.A., 2019. Comparison of the efficacy of ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block, pectoral nerves II block, and intercostal nerve block for the management of postoperative thoracotomy pain after pediatric cardiac surgery. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia, 33(2), pp.418-425.

Gado, A.A., Abdalwahab, A., Ali, H., Alsadek, W.M. and Ismail, A.A., Serratus Anterior Plane Block in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Thoracic Surgeries: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia, pp.S1053-0770.

Man, J.Y., Gurnaney, H.G., Dubow, S.R., DiMaggio, T.J., Kroeplin, G.R., Adzick, N.S. and Muhly, W.T., 2017. A retrospective comparison of thoracic epidural infusion and multimodal analgesia protocol for pain management following the minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum. Pediatric Anesthesia, 27(12), pp.1227-1234.

Altun, G.T., Arslantas, M.K., Dincer, P.C. and Aykac, Z.Z., 2019. Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block for pain management following minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia, 33(9), pp.2487-2491.

Asorey, I., Sambugaro, B., Bhalla, R.J. and Drozdzynska, M., 2020. Ultrasound-guided serratus plane block as an effective adjunct to systemic analgesia in four dogs undergoing thoracotomy. Open veterinary journal, 10(4), pp.407-411.